Architect Avenue

I must confess that I enjoy a deep dive on Zillow or wandering through the open houses on those Designer Home Tours that you see all over the suburbs when a new development pops up. If I go to an estate sale, I am there just much to look around the house as I am for the bargains. If a historic home is going to let me nose around, I’m in. These tours aren’t a modern invention. Real estate developers have been using human nature to market their projects for a very long time. We can see an early example just to the north of Minneapolis.

Announcing the winning name chosen from 2,281 submitted - Columbia Heights

In 1892, most of the land to the north of Minneapolis was undeveloped farmland and railroads. Thomas Lowry bought over 1500 acres in the area and partnered with promoter Edmund Walton to stir up interest for potential land buyers and home owners. They stirred up the public’s imagination and ran a mail-in contest in the newspapers asking readers to submit names for their “Model City”. Hundreds of people submitted and the winner was announced: Columbia Heights.

Since 1892 was the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ voyage across the ocean blue, the year had been dedicated to celebrating the Italian explorer. That year saw the dedication of the land for the Great Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the creation of the commemorative Columbian Half Dollar and eventually led to the celebration of Columbus Day.

Lowry’s real estate development throughout the Twin Cities was in tandem with his other business, the Minneapolis Street Railway. He built streetcars to carry you further and further from the city and developed the real estate along the streetcar lines, giving you a reason to go there.

In 1905, Lowry and Walton announced another contest, inviting architects to design and build homes and the winner would receive a prize of $1500. It would be a utopian street where the homes were to be built and would be called Architect Avenue. Six architects entered the contest and they were all local heavy-hitters:

Fremont Orff

Orff had just completed the county courthouses in Renville County and Big Stone County and would also go on to design the Carnegie Library in Little Falls, the fire station in Perham and the Red Lake County Courthouse.

Lowell Lamoreaux

Lamoreaux had recently finished the Semple Mansion and would soon go on to build the Red Wing City Hall and the T. B. Sheldon Memorial Auditorium. He also built the Eitel Hospital (now apartments and condos) and the Theodore Wirth House where the parks superintendent lives.

William Kenyon

Kenyon was the head architect for the Soo Line railroads and designed many train stations, including the historic train depot in Thief River Falls. He also designed the Janney Children’s Pavilion at Abbott Hospital, the Gluek mansion and other beautiful homes.

Adam Lansing Dorr

Dorr was known for his multi-unit housing like rowhouses and apartment buildings. He designed the West Fifteenth Street Rowhouses and the Ogden Hotel (now apartments). He also designed homes along Lake of the Isles Parkway.

Bertrand & Chamberlain

George Bertrand and Arthur Chamberlin worked together from 1897 to 1931. Together, they built the Northwestern Knitting Company Factory (Munsingwear) that is now the International Market Square. They built the North building of the Minneapolis Grain Exchange and the Minneapolis Athletic Club.

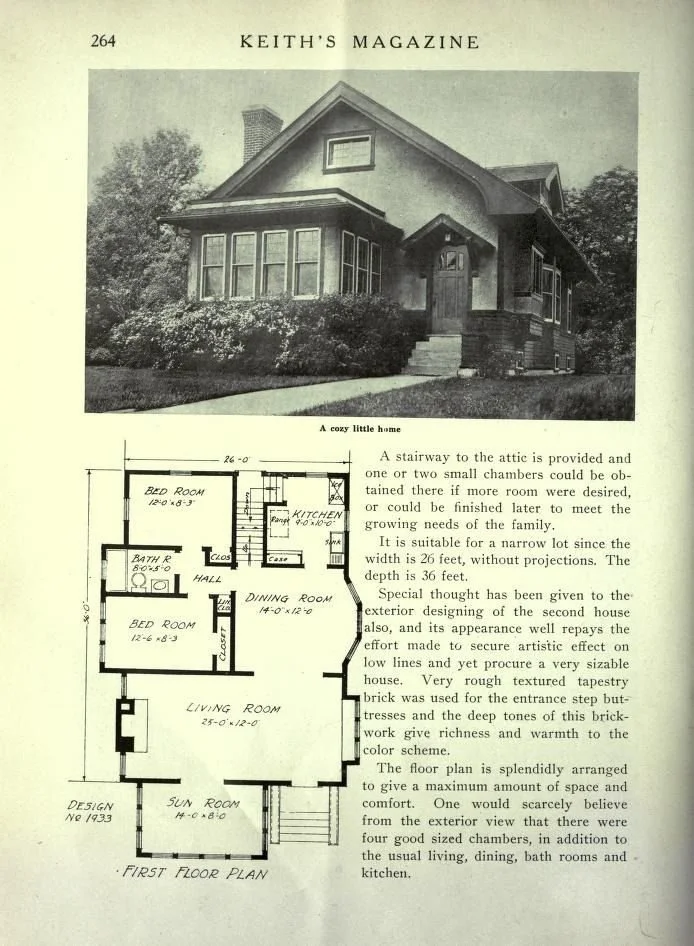

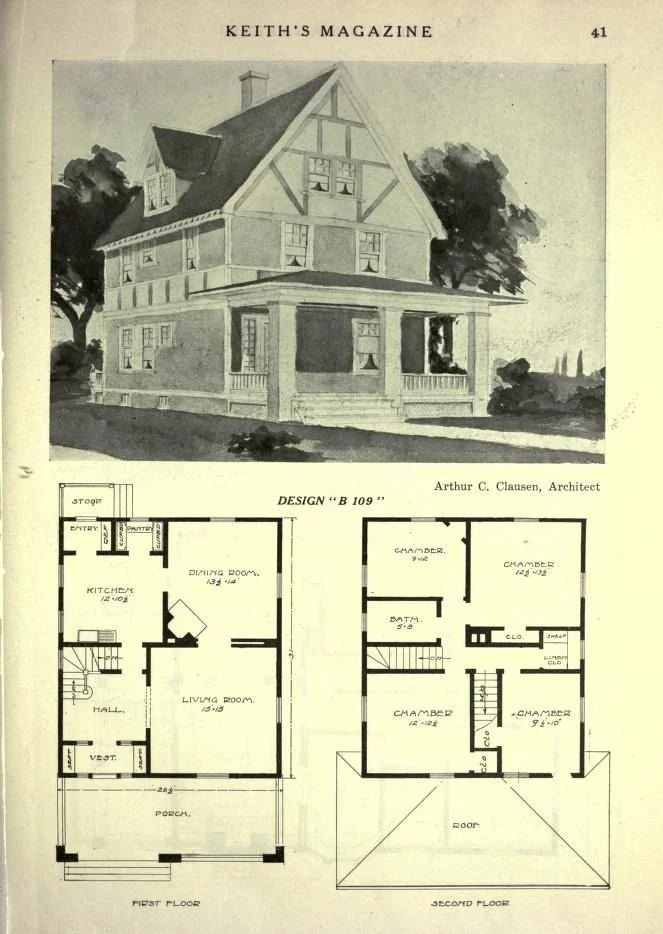

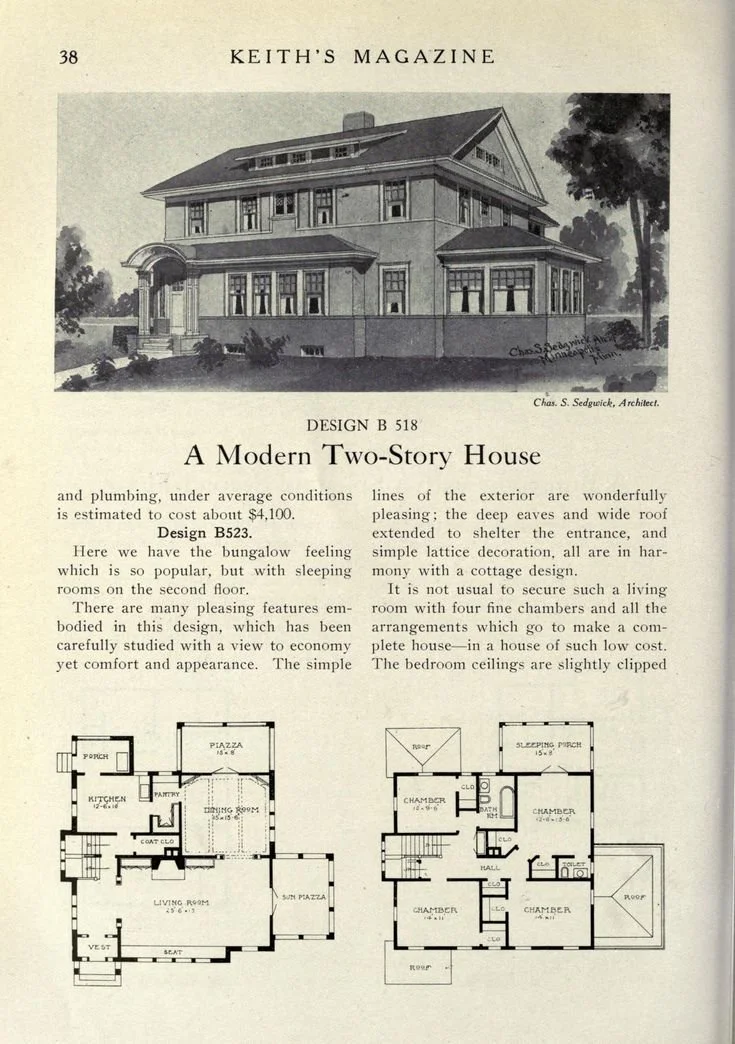

Walter J. Keith

Walter J. Keith’s architecture firm got free advertising when the Minneapolis Journal printed his house designs weekly for a year. Then, when the Ladies Home Journal started printing them, he got nationwide attention. By 1899, he was publishing his own magazines of house plans and bringing in more than $2.5 million in commissions per year. His own home, that he designed and built, still stands at 1908 Kenwood Parkway.

All summer long, the newspapers featured the designs, drawings, and details of the homes while crews of workmen scrambled to get them built. A huge Fourth of July celebration was hosted near the construction site, drawing hundreds to take a free ride on the newly completed streetcar on Central Avenue leading to the progressing neighborhood.

Finally, on September 17th, thousands gathered to see the landscaped lawns, freshly macadamized streets and snooped through the fully finished and decorated homes. They cast their vote for the best designs. One lucky attendee event won a parcel of land in a raffle drawing.

The winner was Walter J. Keith, who seemed to have an advantage with his extensive experience in house design versus his competitors’ more large-scale commercial backgrounds.

Edmund G. Walton

An important side note needs to be made about Edmund Walton’s involvement in the Architect Avenue promotion and sales. Walton and Lowry partnered on many developments throughout the Twin Cities and Walton’s skill at garnering the attention of the public made them all extremely successful.

Walton immigrated from England and arrived in Minneapolis in 1887. He worked as an independent rental agent and realtor and by 1893 was serving as the agent of record for many of Lowry’s land sales.

So it is interesting to note that it wasn’t until 1910 - five years after the development of Architect Avenue and one year after the death of Thomas Lowry - that Edmund G. Walton was the first land developer to introduce the first racial covenant into his Minneapolis real estate deeds. These racist covenants, clauses inserted into the legal ownership documents, prevented the sale to people of certain races. The clauses ranged from the broadly exclusionary ‘persons not of Caucasian race’ to the expressly detailed ‘any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent’.

Did racial inequality in housing start with the implementation of racial covenants? Certainly not. I’m sure Walton was discriminating against immigrants and people of color long before he started putting it in writing. The early 1900s saw a rising tide of racism in Minnesota as many former slaves left the south to escape the Jim Crow laws taking hold there. They continued long after Walton’s death in 1919.

In Minneapolis, these racial covenants were declared null and void by state and federal laws. Minnesota banned them in 1953, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed them nationwide. In addition, there are continuing programs helping homeowners discharge and completely eliminate racial covenant language from their deed documents.

Finally, there is growing effort to rename the street that was named to honor Edmund G. Walton, Edmund Boulevard, in the Longfellow neighborhood. As one resident of the street stated, “Once you know about something you’re responsible for it. That is information that you cannot just cast aside and be blissfully ignorant about. We know this beautiful strip of land we get to live on was named in honor of a racist, hateful person.”

“Symbols are one way that we as a society demonstrate what we care about. Renaming the street is one small step that we as a community can take to say this is not what we are anymore.”

While racial covenants weren’t included in the deeds for Architect Avenue and didn’t play a role in their development, Walton’s involvement and the wealth and power he accumulated from deals like it are all intertwined.

Today

All six of the original homes on Architect Avenue are still standing, though each has a had a few modifications. The rest of the surrounding lots have filled in, too, and the notoriety of the neighborhood’s creation has faded.

Still, we all look forward to the next opportunity to envision a “Model City” and snoop through our neighbors homes.