The Lustron Homes' Minnesota Roots

The row of Lustron Homes on Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis may have caught your eye. Their mid-century modern aesthetic, square enameled-steel paneling, and unique color schemes certainly make them stand out from the more traditional post-war houses around them. Their innovative architecture has been profiled many times, but less well known are the roadblocks that plagued the company and the scandals that brought production to an early end.

At the close of World War II, the United States Government returned its focus to domestic concerns. During the war, any manufacturing or production had been strictly limited to products that benefited the war effort. New building had been completely halted and a backlog of potential homeowners was going to reach critical levels when nearly 2 million soldiers returned home, married and started families. A massive effort was undertaken to meet the housing need. Dozens of companies responded (either to the patriotic purpose or to the massive government funding - or both) and converted their production to the materials in desperate need.

This is where the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Corporation enters the story. Led by Carl Strandlund, “Chicago Vit” had developed Lusterlite Panels that could be used for interior or exterior construction. At the end to the war they had a huge contract lined up to build gas stations using the panels across the country. The government blocked his commercial construction goals by refusing to release the steel the designs required. They told Strandlund he’d be more likely to get steel supply approval for residential building. Strandlund hired architects and designers Roy Burton Blass and Morris H. Beckman to create a new prefabricated design using Lusterlite. Their ingenious designs were called Lustron Houses. To get the homes under construction, Lustron was going to have to overcome three major roadblocks: getting the government to authorize the steel supplies necessary for manufacture, obtaining a factory to build them in, and getting the money to pay for it all.

Factory

It seemed obvious that the headquarters of Lustron would be in the same city as its parent company, Chicago Vit. A former Dodge-Chysler auto plant in Chicago had been under government authority during the war and making aircraft engines. Strandlund requested that ownership be transferred to Lustron, but they were met with unexpected competition. Joseph Tucker and the Tucker Corporation had already contracted the factory and planned to build 100 mph “Tucker Torpedoe” automobiles. He refused to release his contract. In the end, Tucker failed and went bankrupt, but his stubbornness forced Lustron out of Illinois.

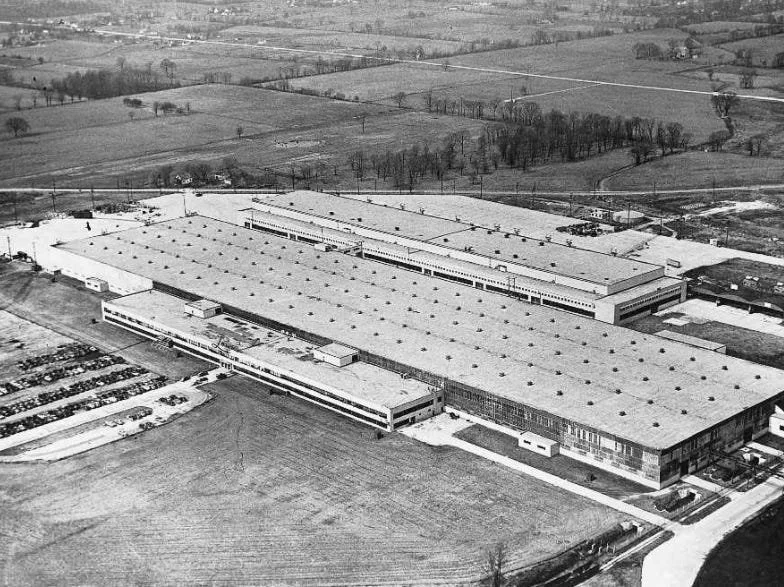

In Columbus, Ohio were two enormous war plants that had manufactured airplanes for the military. After some tense negotiations with North American Aviation, who wanted to lease the entire campus to continue building airplanes, an agreement was reached to share the buildings and Lustron signed a lease. The massive factory emboldened Strandlund to estimate he could build 100 houses per day.

Steel

On the surface it would seem like getting the materials to build the homes would be the most important and most difficult roadblock to overcome, but in reality it was the simplest. President Truman ended price controls on raw materials in November 1946 and the price of steel skyrocketed because of the lack of supply. There was no way that manufacturers were going to be able to balance their budgets if supply costs weren’t brought under control. Strandlund’s confidence in his ability to make a significant dent in the housing shortage swayed the government’s lack of confidence to a supportive position. The Department of Commerce allocated 59,000 tons of steel for housing - not just to Lustron, but a second roadblock was overcome.

Money

The government funding for this enormous country-wide building effort was going to come from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), a government corporation created during the Depression to shore up financial institutions and stabilize the economy. Their initiatives continued during the war to make sure financing was available to achieve the goal of building 2.7 million homes by the end of 1947. This was an emergency effort to quickly move money and resources to meet a need. In hindsight, speed without caution can often lead to disaster.

Facing continued resistance from decision makers, Strandlund swung for the fences and promised he could build 400 houses per day and would produce 30,000 houses in 1947. In return, he needed $52 million dollars from the RFC. Since they only had $54 million TOTAL to spend, they rejected him. He reduced his request to $32 million and they rejected him again. Since Lustron was only planning to put up a fraction of a percent of the funding, the government expected more from Lustron to secure the loan.

Strandlund’s partners at Chicago Vit had already held a stock sale to raise $840,000 to secure the loan, but the government wanted more. Setting the bar at a $3.6 million security, the investment demands became too much for his partners. Strandlund resigned from Chicago Vit and used all of his stock to purchase the Lustron trademark and the machinery designed to produce the homes.

He was granted the loan and thought that this would clear the remaining red tape, but a whole new set of roadblocks sprang up in his path.

A New Set of Problems

Lustron started the arduous and expensive process of retooling and converting the Ohio factory to the specific needs of their housing designs. At the same time, unusual interference began among members of the RFC. A Senate subcommittee started reconsidering the feasibility of the loans even as they granted more funds to cover the growing costs. The RFC “suggested” that their junior loan examiner Merl Young be hired by Lustron and promoted to Vice President to oversee the loans. They also “suggested” that RFC member Walter Dunham be appointed to Lustron’s Board of Directors.

Pep Talks and Team Players

As the factory gathered steam and hard work was begun, Strandlund revealed his passion for football and often visited the production floor to deliver passionate pep-talks to his players. He made big predictions, laid out big plans and motivated the workers to work even harder.

Strandlund’s football fandom had started when he lived in Minneapolis in the 1930s. He had worked for a decade at the Minneapolis-Moline Farm Equipment Company. He had attended games at Memorial Stadium and seen the Golden Gophers win National Championships in 1934, 1935, and 1936. He never attended classes at the University, but he was as loyal as any graduate. He even became involved with the alumni association, made large donations, and actively worked to recruit players for the team. By the time he established his office at the factory in Columbus, he hung a portrait of the Gopher’s coach, Bernie Bierman on his wall next to one of President Truman. He hired Vern Oech from the 1934 and 1935 Championship team to be his assistant sales manager.

The factory also annually hired active Gopher players to work during the summers. The men lived in a fraternity house on the Ohio State campus and even worked out on the Buckeye’s practice fields. This certainly got under the skin of their conference rivals in Ohio whose boosters tried to stir up trouble claiming the Gophers were being paid a lot of money for little work. Reporters searched out Coach Bierman on vacation in California to press him on the appropriateness of this arrangement.

As it turned out, Lustron was also employing several players from Ohio State, former Buckeye player Tarzan Taylor, and the former Northwestern coach, Dick Hanley. There may have been some favoritism in hiring football players, but least Lustron wasn’t favoring just one team.

More Money, More Problems

As the first homes rolled off the production lines, Lustron was barely covering costs. Two more loans from the RFC had brought the total to $32.5 million. The peak of the housing demand was passing as more traditional builders were stepping in while Lustron worked out its production kinks. Costs were rising as transportation proved more expensive than anticipated and in some locations, like Minnesota, different building codes required design modifications that increased the price.

The tide of opinion, both public and official, was turning and pressure was increasing. As yet another loan brought Luston’s loan totals to $34.5 million, a senate subcommittee reframed the reasons Merl Young had become an executive at Lustron. Suddenly, all memory of the RFC “suggestion” behind his hiring was forgotten and it was inferred that his high salary was a reward Young’s influence in securing the initial loans. But still, more loans brought the total to $37.5 million.

Lustron was in an untenable position. To finish innovating the production processes and transportation lines necessary to deliver on their promises they needed money. They had not yet reached the output necessary to break even and start to pay the government back. Yet the government had run out of patience, was spreading negative publicity about the costs expended on the scheme and its leadership, and public opinion was turning against them. Even with huge contracts to build Lustron homes on military bases and in the suburbs of Chicago, Lustron was losing momentum.

Still seeking solutions, Strandlund realized that the remaining roadblock they needed to face was on the consumer end of the financing scheme. Lustron homes were sold to local dealers on a cash basis, but the homebuyers were applying for FHA loans to mortgage their purchase. Since the homes were manufactured, shipped, and built in three days but it took up to 60 days for an FHA loan to get approved the dealers were caught in the middle and needed deep pockets to bridge the gap. They didn’t have that money, so hundreds of finished houses were sitting crated at the warehouse waiting to be sold. Lustron was forced to lay off hundreds of workers and they fell even father behind from breaking even.

Strandlund desperately tried to fill the gap. He created the Lustron Mortgage Company and boldly asked for a $14.5 loan from the RFC to provide funds to local dealers. He was still holding out hope that he could make it work. The senate did not have the same faith and started foreclosure. A receiver was appointed and the first step was to reduce payroll. By firing Strandlund in the first round of cuts he was able to reduce payroll by $50,000 (about $660,000 today). The government ordered all company assets sold and Strandlund filed for bankruptcy and in a settlement turned over the patent to the Lustron process, all of the designs, and all of his stock in the company. He was forced out and the RFC was in total control. This seemed like the end, but it wasn’t. This is where the story takes a bizarre turn into politics and the fate of the Lustron homes was decided by a completely unrelated war between politicians.

The Department of Justice launched an investigation into the company after discovery of a $10,000 ($140,000 today) payment that had been made by Lustron to the Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy had written an article to be used in Lustron promotional materials. McCarthy didn’t deny the payment and claimed it was nothing out of the ordinary, just a fee for services rendered (even though the article had been completely written by someone else and McCarthy just put his name on it). Strandlund had also allegedly hosted McCarthy at Pimlico where Strandlund’s horses were running. McCarthy placed several bad bets and Strandlund covered his losses. Unfortunately for Lustron, McCarthy was an intensely controversial figure in American politics and deeply disliked by nearly everyone. He had made claims of communist infiltration into the State Department, the military, even the White House. His sham investigations and conspiracy theories disrupted government, ruined careers and even ruined lives. For years, any time a list of McCarthy’s abhorrent acts was published the Lustron “bribe” was prominently featured.

Another black mark against Lustron in the public eye was the revelation that Merl Young, the loan examiner hired by Lustron to provide oversight and protect their financial interests had received a pay bump from his RFC salary of $6,500 a year to a salary of $18,000 at Lustron. The probe also found that while he was on Lustron’s payroll, he was also receiving a $10,000 salary from another company that received RFC funding. Young’s wife, a secretary in the White House, had been gifted a $10,000 mink coat by yet another firm seeking RFC funding. Young claimed that he repaid the firm, but was eventually convicted of perjury.

The probe also alleged that a conspiracy among the RFC stakeholders existed to force Strandlund to turn over the Lustron Corporation to their control for personal benefit. An extremely complicated web of connections, deals, and backroom agreements revealed that the so-called “government oversight” wasn’t “seeing” much.

All of these conflicting motives had cut short the time Lustron needed to reach peak production, fill their orders, and pay back their loans. The whole dream was doomed to fail. The fact that over 1,500 Lustron Homes of the 2,600 produced still stand today is a testament to their design and durability. It wasn't the product that was the problem, it was greed and mismanagement.

Back to Minnesota

Decades later, Clara Strandlund, widow of the Lustron founder recounted to a Minneapolis Star Tribune reporter how the collapse of the business had completely changed her husband. They sold their home and Lustron guest house in Columbus and lived in a few different cities before returning to Minneapolis in 1974. They were living in a condo in Edina when Carl Strandlund passed in on Christmas Eve of that year. Carl and Clara were both laid to rest in the Lakewood Cemetery.

Eighteen of the 29 Lustron Homes built in Minnesota are still standing today. South Minneapolis has the most (7), but there are also homes in St. Anthony, Robbinsdale, Austin, Minnesota City, Rochester, St. Cloud, Wadena and Winona. Over 50 Lustron homes are on the National Register of Historic Places and dozens more have other local protections.

It’s a shame that today, with the nation again facing dire housing needs at the same time we see a resurgence of love for mid-century modern design and nostalgia, that the Lustron Homes weren’t more successful in their time or still in production today.